“I had to go out and get me one.”

Sixteen-year-old Windy Gallagher of Griffith, Indiana wrote in her journal that October 13, 1987 would be a “no worries day.” Around six-thirty that evening, her older sister Christine came home, warmed up some pizza, and watched a little television. She assumed her sister was asleep in the room they shared (Shnay). When she went into the room, she found Windy’s body on a bed. Her hands were tied behind her back. She was naked from the waist down, and her bra was pulled up over her breasts. She had been stabbed twenty-one times; her intestines were pulled from her body. The apartment showed no evidence of forcible entry.

Three months later, eight-year-old Jeremy Colhouer of Land-o-Lakes, Florida, returned from an outing with his father and young sister. He went to his room to get his shin-guards for soccer practice and found the partially nude body of his fourteen-year-old sister, Jennifer, raped, strangled, and disemboweled. She still wore her socks and sneakers. Her hands were bound. The house showed no evidence of forcible entry.

On the afternoon of March 22, 1988, Beaumont, Texas police officer Paul Hulsey, Jr. spotted a known drug dealer riding in a red Corvette driven by an unknown man. He attempted to follow, but the driver of the Corvette sped away. Hulsey later located the Corvette in the parking lot of a Best Western Motel. When he attempted to question the car’s owner, Hulsey was shot dead. The Corvette and its driver escaped.

After ditching the Corvette, Michael Lee Lockhart paid a cab driver $100 to take him to Houston. When the police pulled the cab over, fifty miles outside of Beaumont, he reportedly told the driver, “Oh, well. I guess I’m going to jail now.” (Michael Lee Lockhart #430)

When first arrested, Lockhart was cooperative and freely admitted shooting Husley. He did not, however, accept responsibility. It was Husley’s own fault, he claimed, for coming into the hotel room without a back-up. A day later, Lockhart turned angry and combative and refused to cooperate further with police. He’d seen a newspaper article in which the police referred to him as a drug dealer and was deeply insulted. (Morrison, 206-207)

After his Texas arrest, bloody handprints, DNA evidence, and suspect sketches linked Lockhart to the murders in Griffith and Land-o-Lakes. In November 1987, almost midway between the murders of Gallagher and Colhouer, Lockhart visited his ex-wife. For two days, he kept her bound and gagged and repeatedly raped her.

Lockhart was known for good looks and charm. The assistant principal of his former high school called him “a born salesman.” A friend from his teenage years said, “He could B.S. his way out of anything.” (Ramsdell and Torry) According to Lockhart, he could also B.S. his way into anything. He convinced Windy Gallagher to let him into her home to make a phone call. She gave him a glass of water. He told Jennifer Colhouer he was a real estate agent—there was an empty house a few doors away—and needed to use a phone. “I still can’t believe how easy it was. I could pretty much pick up anyone off the street, and they would follow me anywhere like a little puppy dog,” he told psychiatrist Helen Morrison. (Morrison, 202-211)

When asked by Morrison to describe the day leading up to Colhouer’s murders, Lockhart described it as an average day. He woke up late and took a shower. “I was in the shower washing up,” he said. “And then it hit me. I had to go out and get me one.” (212) He later told others that on the morning of Gallagher’s murder he woke up depressed and suicidal, “and if I was going to die, then I was going to kill somebody too.” (Michael Lee Lockhart #430)

Early reports described Lockhart, the ninth of ten children, as the “model All-American boy” (Ramsdell and Torry) and his family life as happy. Later, a sister testified he was a “sweet” child, who “never did anything wrong,” while a brother testified that Lockhart often witnessed fights and abuse between their parents (Fox). Morrison states there is no evidence of sexual abuse in Lockhart’s childhood (209). A psychologist testifying for the defense at his Texas trial said Lockhart was molested by a family friend at the age of five or six and the victim of incest between the ages of nine and twelve (Michael Lee Lockhart #430; Haines).

Lockhart received the death penalty in Texas, Florida, and Indiana for the murders of Hulsey, Colhouer, and Gallagher. Authorities credit him with at least three more murders of teenage girls and consider him a possible suspect in more. Lockhart claimed to have committed over two-dozen murders. He later changed his story, accepting responsibility for only the three killings for which he was convicted.

While reading about Lockhart and his teenaged victims, I was reminded of the Joyce Carol Oates story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” first published in 1966, two decades before Lockhart killed Gallagher and Colhouer. If Lockhart is to be believed, he had a much easier time convincing his victims to open the door than Arnold Friend did, but the images of Friend with his gold car and Lockhart with his red Corvette, as archetypes of evil, seducing young girls through a screen door remains and horrifies.

On December 9, 1997, Michael Lee Lockhart was executed by the State of Texas for the murder of Officer Hulsey. His last meal was the All-American double-cheeseburger, fries, and a Coke.

Works Cited

Fox, Kym. “Lockhart had bad childhood, relatives claim.” Toledo Blade 20 Oct. 1988: 21. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Haines, Renee. “Defendant abused as boy, witness says.” Houston Chronicle 10 Oct. 1988: A13. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

“Michael Lee Lockhart #430.” Clark County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Morrison, Helen, and Harold Goldberg. My Life Among the Serial Killers: Inside the Minds of the World’s Most Notorious Murderers. New York: Harper Collins, 2004. Print.

Ramsdell, Melissa, and Jack Torry. “Saga of Wallbridge’s Michael Lockhart: Did ‘all-American boy’ become a killer?” Toledo Blade 26 June 1988: A1, A4. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Shnay, Jerry. “Girl Tells Of Finding Body Of Slain Sister.” Chicago Tribune 15 June 1989: n.pag. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Other Resources

Associated Press. “Policeman’s killer given death penalty.” Houston Chronicle 26 Oct. 1988: A17. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Goffard, Christoper. “In the name of his sister.” St. Petersburg Times 23 Jan. 2000: n.pag. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Graczyk, Michael. “Inmate with death sentences in three states put to death.” Abilene Reporter-News. Associated Press, 10 Dec. 1997. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

“Michael Lee LOCKHART.” Murderpedia, the encyclopedia of murderers. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

Sullivan, Erin. “Family suffers another loss.” St. Petersburg Times 27 July 2007: 1. Web. 9 Nov. 2012.

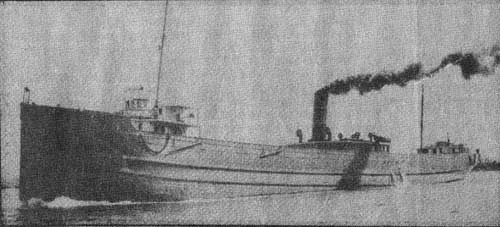

In the winter of 1909, the Marquette & Bessemer No. 2 left port at Conneaut, Ohio headed for Port Stanley, Ontario. A steel car ferry, the ship carried railroad cars filled with coal. She made the five-hour Conneaut to Port Ontario run daily. On December 7th, she never made her destination. Caught in a winter storm, the ship is rumored to have spent two days traveling back and forth between Conneaut and Port Stanley, unable to make it into harbor. Nobody knows where or when she sank, and she remains one of the two undiscovered shipwrecks of Lake Erie.

In the winter of 1909, the Marquette & Bessemer No. 2 left port at Conneaut, Ohio headed for Port Stanley, Ontario. A steel car ferry, the ship carried railroad cars filled with coal. She made the five-hour Conneaut to Port Ontario run daily. On December 7th, she never made her destination. Caught in a winter storm, the ship is rumored to have spent two days traveling back and forth between Conneaut and Port Stanley, unable to make it into harbor. Nobody knows where or when she sank, and she remains one of the two undiscovered shipwrecks of Lake Erie.